When the National Lung Screening Trial (2002–2004) revealed that low-dose computed tomography (CT) screening reduced lung cancer mortality in a landmark study published in a 2011 New England Journal of Medicine article, healthcare providers struggled with how to provide that screening to rural and underserved communities.1,2

Although research suggests that cancer screening is effective in reducing cancer mortality, particularly for lung and breast cancer patients, many patients in low-income settings lack access to adequate public transportation or are unable to take leave from work to receive preventive healthcare services typically provided at urban healthcare centers. These disparities are particularly significant when you consider that cancer is the second leading cause of death in the US, accounting for nearly 600,000 deaths annually. In 2021, an estimated 281,550 women were diagnosed with breast cancer and 14,480 with cervical cancer. In addition, 149,500 men and women were diagnosed with colorectal cancers.3

A report issued by the Biden Administration in May 2022 outlined the goals of its Cancer Moonshot initiative, which aligns with the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer’s screening recommendations and includes equitable cancer screening as a key objective.4,5 The private sector’s response includes the development of new and expanded mobile cancer screening programs, which typically provide services to uninsured patients and those in government-sponsored plans.5

“Mobile screening vehicles that bring cancer screening directly to people where they live and work are an important way of expanding the reach of lifesaving healthcare efforts,” said Heidi Nelson, MD, FACS, Medical Director for ACS Cancer Programs. “We know cancer screening saves lives, and we know that not all our citizens can travel to healthcare facilities. Mobile screening helps close the gap and ensures we reach as many people as possible.”

This article describes two pioneering mobile cancer screening programs: the Catholic Health Initiative (CHI) Memorial Hospital’s Breathe Easy program in Chattanooga, TN, which is acknowledged in the Cancer Moonshot initiative’s “Private Sector Fact Sheet,” and the Bassett Health Network Cancer Services Program mobile coach in Cooperstown, NY, one of the first traveling screening initiatives in the US.

CHI Memorial Hospital’s Breathe Easy Program

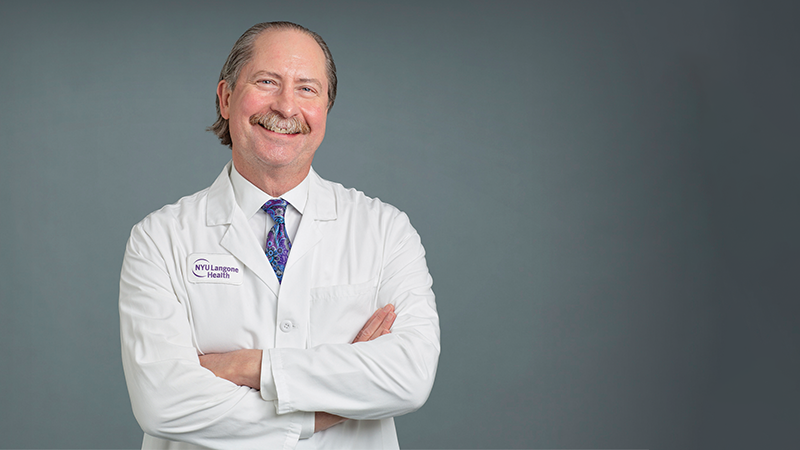

The Breathe Easy Mobile Lung Screening bus took to the streets in 2018 and serves 14 counties in Tennessee, eight counties in northern Georgia, and two counties in northeast Alabama.6 “In our state of Tennessee, we have one person dying every 2 hours of lung cancer,” said Rob Headrick, MD, MBA, FACS, chief of thoracic surgery at CHI Memorial Hospital.

“Fortunately, there are steps that you can take, beginning with removing the stigma around lung cancer and offering quick and accessible screening to those in need.” In fact, Dr. Headrick’s father, also a well-known thoracic surgeon and a smoker, refused to be x-rayed because of the accepted medical assertion at the time that diagnosing lung cancer early had no benefit. “What they didn’t understand at that point in time is that it still takes a pretty large tumor to be seen on a chest x-ray,” said Dr. Headrick.

“One of the great things about medicine is that there’s no finish line, there are always new things to discover. One of the things the National Lung Screening Trial showed was that if you find cancer early, not through a chest x-ray, but through a CT scan, it does change the prognosis,” he said. “And the treatment went from something complicated, expensive, and terrible to something that was relatively simple—simple meaning we were already in the minimally invasive world of surgery.”

CHI Memorial’s Breathe Easy mobile lung bus allows healthcare practitioners to take low-dose CT lung screening to areas where at-risk individuals may have limited access to this scan otherwise. Individuals who are at highest risk for lung cancer and are ideal candidates for low-dose CT screening include:

- Current or former smokers

- People ages 50–80 who have smoked for 20 years (one pack per day or more)

- People who quit smoking within the last 15 years

“I thought that after the National Lung Screening Trial, I was going to be inundated with people just jumping into my office, saying ‘Give me this scan!,’ and yet nobody showed up,” said Dr. Headrick. “Here’s the problem—our healthcare system doesn’t educate people as to why they should engage in their healthcare. I realized that I have to go where the people are and that I have to make healthcare simple.” In fact, the project became known as “Breathe Easy” to convey Dr. Headrick and his team’s goal of reassuring patients through the screening process by educating them about optimal patient care.

The initial mobile bus prototype included a portable CT scanner, independent power, and climate control among other features, and cost $650,000 to build. Funding to build the vehicle, which included a Winnebago shell and freightliner chassis, was donated through the CHI Memorial Foundation, with additional funding provided by CHI Memorial, Medical Coaches, and Siemens.

Researchers examined patient data from the 10 months that the prototype bus was in operation in 2018. According to a study published in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery in 2020, the Breathe Easy coach traveled to 104 sites and screened 548 patients.7 For these patients, the mean age was 62 years old, with a mean smoking habit of 41 years. Significant pulmonary findings were seen in 51 patients. Five lung cancers were identified—four of them at an early stage. In addition, nonpulmonary results also were found in 152 of the individuals screened, with the most common being moderate-to-severe coronary artery disease in 101 patients.7

Bassett Health Network Cancer Services Program Mobile Coach

Since 2008, Bassett Healthcare Network (BHN) mobile coach has provided tens of thousands of breast, cervical, and colorectal mobile screenings and referred hundreds of patients for additional care, according to Alfred Tinger, MD, FACRO, medical director of Bassett Cancer Institute in Cooperstown, NY, and Mark Kirkby, supervisor for Cancer Services Programs of the Central Region. The recreation vehicle (RV)-type medical coach, through the fundraising efforts of the Friends of Bassett and other leading donors, has traveled the 5,600 miles that Bassett serves, screening the uninsured and underinsured in Otsego, Oneida, Delaware, Chenango, Madison, Herkimer, Schoharie, Fulton, and Montgomery counties.8,9

“This is an imperative project for this area because patients have a hard time getting to screening,” said Dr. Tinger, who became medical director in 2019. “The one thing about the mobile coach that a lot of people don’t understand is that patients would rather go there than to a clinic because they view it as a one-stop shop. We eliminate driving for patients. We eliminate parking issues. We eliminate them having to use sick time or personal time to go to appointments because we go to their community, and we pull up on their doorstep,” added Kirkby.

In 2017, after more than a year off the road, the Bassett program replaced its original vehicle with a new-generation RV-type mobile coach complete with state-of-the art diagnostic technology, including 3-D mammography—an imaging test that combines multiple breast x-rays to create a complete image of the breast.10 The new coach, built by Medical Coaches, had a price tag of approximately $1 million paid for by fundraising efforts of the Friends of Bassett, New York Central Mutual Fire Insurance Company, and other donors. “New York state provides funding to screen patients for free, but Bassett pays to maintain the coach,” said Dr. Tinger. Maintaining Bassett’s medical coach costs approximately $1.1 million per year.

In 2018, a year after the launch of the new mobile coach, 1,428 mammograms were performed on the vehicle. In 2019, 1,375 mammograms were performed, with 1,202 performed in 2020, and 1,195 mammograms performed in 2021. From 2018 to July 2022, 219 cervical screenings were performed via the coach, and 237 colorectal screenings (fecal immunochemical tests, also known as stool screening kits, as well as colonoscopies) were also provided.

The Patient Experience

What happens if a patient has an abnormal result via a mobile screening? How are the results and follow-up treatment options presented to the patient in such a way that they feel informed and educated on next steps?

“Typically, the patient receives results within 24 to 48 hours. It’s a fairly quick turnaround,” said Kirby. “There are some days where they actually have results within a few hours. We prefer reaching out to patients with phone calls for personal updates, rather than a text or an email.”

“We have a nurse navigator who works on the coach and is responsible for speaking with the patients; if anything is positive, the nurse arranges for further workup with biopsy or referrals to specialists,” added Dr. Tinger.

In the Breathe Easy program, “Patients will get a phone call that day if there’s a positive finding, and we’ll try to talk them through it, so they’re not scared,” Dr. Headrick said. “If we find something on somebody today, they’re going to be offered a same-day appointment to be seen in the office.” If a patient happens to live closer to another medical center, Dr. Headrick’s team contacts that facility to expedite the follow-up appointment.

As for contacting patients with normal scan results, CHI Memorial Hospital’s Breathe Easy program partnered with Rhinogram, a cloud-based virtual care platform that connects clinicians and patients with text and video messaging in real time, to send text messages that are compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act’s (HIPAA) privacy rules. “Nobody wants to answer their phone if they see a hospital ID come across with all the spam calls,” explained Dr. Headrick. “Everybody views a text message in which we give them the basic message of, ‘You don’t have cancer. Here’s your calcium score. Click on this link for an in-depth discussion.’”

Harnessing the power of technology, like HIPAA-compliant text messaging, is one of the most cost-effective ways to scale-up mobile cancer screening capabilities. “If we’re going to make headway with our program, we’ve got to go from scanning 3,000 people to 30,000 people. And when you do that, you can’t afford the salaries and benefits that go along with adding a call center of individuals that are relaying normal scan results,” Dr. Headrick said.

Dr. Headrick’s goal of expanding the Breath Easy program—they are adding a second bus in January 2023—led to a request from the White House to participate in the Cancer Moonshot program in May 2022. “That was probably the biggest honor I’ve received in all of my career,” said Dr. Headrick. “When you are sitting there with the highest office of our government that is recognizing what you’ve put together; well, it really energized me. It was a tremendous honor for our community and all of the people who believed in this project.”

Replicating the Breath Easy program model for other areas of the country, including fundraising and developing partnerships with manufacturers and community stakeholders, is a key component of the program’s involvement in the Cancer Moonshot initiative, according to Dr. Headrick.

SDOH

The patient’s experience with mobile cancer screening services often is tethered to social determinants of health (SDOH) and the obstacles certain communities face in accessing preventive care.

The Healthy People 2030 report defines SDOH as “the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.”11 More specifically, barriers to cancer screening can include unreliable or inaccessible transportation, as noted earlier, as well as insufficient housing, food insecurity, and language and cultural barriers.

“The Bassett Research Institute is well-known nationally for studying SDOH and has lots of data on these issues,” said Dr. Tinger. “Most of our barriers are related to socioeconomic or cultural factors.”

“Let me give you a quick example,” added Kirkby. “Our area is heavy populated with the Amish community. The Amish, who typically do not have health insurance, are hesitant to receive preventive healthcare services, such as cancer screenings, due to cost and because they tend to reject any assistance from the state of New York. When we take the time to explain the benefits of early cancer detection, along with the fact that this is a state-funded program held by Bassett and that Bassett is the entity conducting the screenings, these facts seem to make members of this community comfortable enough to get their mobile cancer screenings through us.”

Dr. Headrick noted that some challenges inherent to the healthcare system may discourage some underrepresented populations from engaging with providers of care. “The bus allows us to bring cancer screening to the community, so that when you help patients overcome their fear and uncertainties, we are able to scan them right then and there. You can’t say, ‘Show up next week, drive an hour somewhere else.’ They’re not going to do it.”

In an article published in the June issue of the Bulletin, “The Role of Social Determinants of Health on Cancer Screening,” authors Fedra Fallahian, MD, Dr. Nelson, and Susan Pories, MD, FACS, issued a call to action for physicians to educate eligible patients on how to access preventive services covered by Medicaid and Medicare and endorse policies and legislation that increase access to care.12

COVID-19

More than one-third of adults failed to receive recommended cancer screening in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.13 More specifically, a national survey published in JAMA Network Open found that “between 2018 and 2020, past-year breast and cervical cancer screening prevalence declined by 6% and 11%, respectively.”14 This deficit in cancer screening could result in cancers diagnosed at a more advanced stage and an increase in cancer-related mortality.15

While state-specific regulations for travel and indoor business varied widely during the height of the pandemic, resulting in confusion and hesitancy for some patients regarding in-person medical appointments, the Breathe Easy Mobile Lung Screening bus program realized an opportunity to provide safe preventive healthcare.1

“When the country shut down, we were determined to continue to be there for the community,” said Dr. Headrick. Individuals interested in receiving a cancer screening were invited to drive up to the bus, with a limit of one patient on the vehicle per visit. The Breathe Easy Mobile Lung Screening bus, which was originally outfitted with an air filtration system, was thoroughly cleaned between patient screenings. “I knew we could keep the bus a safe environment. I think we may have been one of the only screening programs that didn’t shut down in the country,” he said. “Last year, at a time when the world was still partially shut down due to the pandemic, we screened 1,600 people on the bus. Our goal this year is 3,000 people.”

While the Bassett Healthcare Network mobile coach was in operation for only 4 months in 2020 (January to April) because of COVID-19 safety protocols, the program offered a notable number of screenings during that brief period. More than 1,200 patients were seen on the mobile coach in more than 24 towns in six counties.

Lessons Learned

According to Drs. Headrick and Tinger, best practices for developing a mobile cancer screening unit could include:

- Equipment: Collaborate with engineers and medical technology professionals and obtain clinical input to overcome potential operational challenges. For example, some mobile screening programs require a CT scanner that can function in a climate-controlled vehicle traveling hundreds of miles over uneven roadways and rugged terrain.

- Driver: Partner with a driver who has a commercial driver’s license, if appropriate. For example, the Breathe Easy bus has a 27,500 pounds gross vehicle weight and requires a driver with this type of training.

- Staff: Select healthcare professionals who are passionate about cancer screening and are outgoing and comfortable functioning in this setting due to the enhanced patient education component inherent to these mobile cancer screening programs.

- Radius: Ensure optimal patient follow-up by creating a plan for service that will entail a travel time of no longer than 1.5 hours.

The models established by the CHI Memorial Hospital’s Breathe Easy Program and the Bassett Health Network Cancer Services Program mobile coach—and others like them—suggest that traveling cancer screening initiatives diagnose some cancers earlier leading to reduced mortality rates. In fact, numerous established and newly launched traveling cancer screening programs across the US are saving lives by providing increased access to preventive care, particularly for rural and uninsured individuals.

“I hate going to the doctor just as much as anybody else does because it typically takes half a day,” Dr. Headrick said. “If we can offer a 10-minute visit through a mobile cancer screening program, people will see real value in what we are providing. The question is—how do we scale this up? We need to consider how this format will work in other regions of the country.”