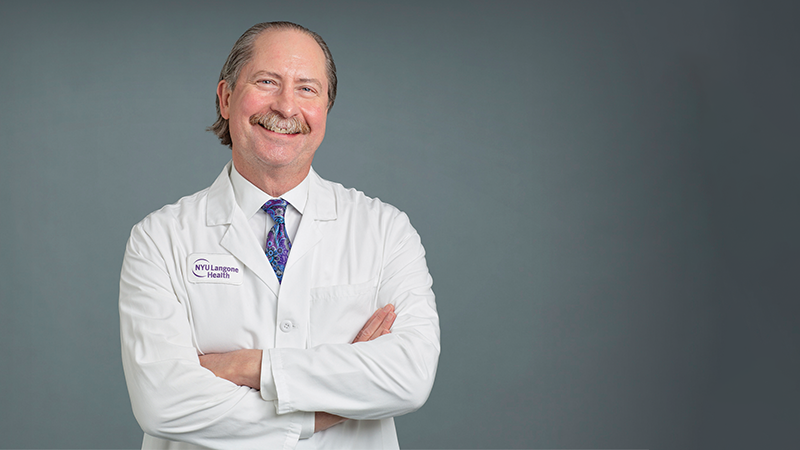

Robert A. Montgomery, MD, DPhil, FACS, has never played by the rules. As a survivor of several near-death experiences, including seven cardiac arrests, and a surgeon innovator, one could say he has both defied and redefined them. His life story is one of resiliency, second chances, and the value of risk-taking.

His first near-death experience came when he was a teenager, while working at a sewage plant. A crane operator moving large concrete blocks hit Dr. Montgomery across his torso and knocked him through a form for a new tank, straight into a skimming vat full of raw sewage.

“Thank goodness that form gave way, or I would have been crushed. My legs caught on that form, and I ended up floating on my back in raw sewage,” he said. “They immediately removed me, took me to the decontamination room, and hosed me down. It was a humbling first job, for sure. But they gave me a half-day off.”

Not only did he earn that time off, but he also learned a higher lesson.

“Beside the sewage plant, we would work jobs high off the ground, which was exciting for a 16- or 17-year-old kid, but we worked alongside men who were 50 and 60 years old, who had been doing this work their whole lives,” he said. “I just remember thinking, ‘I don’t know if I could do this kind of physically taxing work my whole life.’ They were remarkable men, but it was a good lesson to stay in school and pursue something where you didn’t have those physical demands.”

Life lessons are like mileposts in Dr. Montgomery’s journey. The deaths of his father and later his brother revealed a genetic heart condition that inspired a groundbreaking career in organ transplantation. His own heart transplant, which involved an organ donation from a patient who died from a drug overdose and had hepatitis C, gave him a renewed vigor to challenge the notion that one human needs to die so another can live.

“Bobby Doesn’t Think the Rules Apply to Him”

Dr. Montgomery’s proclivity for thinking outside the box was apparent from an early age. As a second grader, Dr. Montgomery went home with a mediocre report card. He was a good student, but the nuns at his Buffalo, NY-area Catholic school noted that he lacked a certain discipline to reach his full potential.

“They wrote in my report card that ‘Bobby doesn’t think the rules apply to him,’” he said. “So, it wasn’t working out with the nuns, and I wasn’t long for Catholic school. Most of my time there was spent being punished in the corner facing away from everyone, so I wasn’t getting much out of it anyway.”

The youngest of four boys, he described a normal, happy childhood, particularly after his family moved from Buffalo to Philadelphia, PA, where he attended less stringent public schools. In his early teens, his 50-year-old father suffered heart issues, including several cardiac arrests and resuscitations. As a result, Dr. Montgomery spent many afternoons doing his homework in his father’s hospital room. Eventually, his mother had a crucial conversation with the physicians after a series of drugs had minimal, if any, impact.

“She said, ‘None of this is working, so what’s left to try?’” he explained. “There was heart transplantation at the time, but this was 1976, and the doctors told her it wasn’t available to anyone over 50 and it still didn’t work that well anyway. I remember thinking, ‘Why doesn’t it work? Why isn’t this an option?’”

Shortly after that conversation, Dr. Montgomery’s father had a final heart attack that left significant brain injury and put him in a vegetative state. Several months later, he contracted pneumonia and died.

“Before he died, he prepared me to help take care of things around the house, paying bills and that sort of thing,” Dr. Montgomery said. “He didn’t talk much about his experiences or his illness, but one day he told me, ‘You shouldn’t be afraid of dying; it’s not a bad thing.’ It’s not what a 15-year-old boy wants to hear, but that was my reality.”

It also was his first lesson in resilience.

Genetic Condition Revealed

Years later, when 27-year-old Dr. Montgomery was an intern at The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, MD, his 35-year-old brother died while waterskiing, which confirmed a genetic heart condition. As a result of this familial cardiomyopathy, Dr. Montgomery had a defibrillator implanted.

He was unsure if he could become a surgeon, as it was unclear then whether the equipment in the operating room would interfere with the device. Thankfully, he was safe for surgery. Among other achievements, Dr. Montgomery has:

- Performed approximately 2,000 kidney transplants

- Pioneered kidney paired donation chains, now responsible for more than 1,000 transplants in the US each year

- Co-developed the laparoscopic donor nephrectomy

He is in the 2010 Guinness World Records for performing the most kidney transplants in a day. In 2009, as director of The Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center, Dr. Montgomery led a four-hospital, 16-person “domino kidney transplant” procedure, in which eight incompatible familial donors gave their organs to strangers so their loved one could receive a compatible organ in return. Several of his operations have become story lines for the TV drama Grey’s Anatomy.

While he has saved many patients’ lives, the defibrillator has saved his life on numerous occasions: hiking in the Andes, at the Broadway show School of Rock, and at a medical conference in Italy. It was after that medical conference in 2018 that Dr. Montgomery was hospitalized in Italy and even given last rites by a priest. He checked out against medical advice and returned to his own transplant program at NYU Langone Health in New York City.

“I knew it was time. I couldn’t afford to wait anymore,” he reflected.

“That’s What Leaders Do”

So, the transplant pioneer became a transplant patient in his own program. He would be operated on by surgeons whom he had recruited and hired. But first he had to find a heart.

“People have to be in very, very bad shape to receive a transplant, and about half of those people don’t make it,” he said. “And to receive an organ, you must be lucky. For me, I’m a large guy and I need—no pun intended—a big heart, so it wouldn’t be easy to find a match.”

Dr. Montgomery was careful he did not receive favoritism. He specifically asked to receive a heart from a hepatitis C patient, found often in opioid overdose cases. Dr. Montgomery had been working on a program to transplant hepatitis C-positive organs in patients who did not have the virus, knowing they’d contract the disease, which was becoming easily treatable with medications. He was the 17th subject in that trial.

“We were discarding all these hep C hearts from perfectly good donors, when we could save more lives,” he said. “I was aware at the time that my taking a hep C heart would set an example for something that I really believed in, but that’s what leaders do. But it was also preemptive survivor’s guilt—that if I took a perfect organ, I would be taking it from one of our other patients.”

Dr. Montgomery waited about 2 weeks as a patient in the intensive care unit. It was then that a 25-year-old man with hepatitis C died from a heroin overdose in a neighboring state. The transplant team prepared for surgery.

“It was a little bit surreal,” said Deane E. Smith, MD, FACS, who was on his surgical team. “It was almost like we were unconscious. Obviously, we knew that this was our boss, the leading pioneer in transplantation, but from the time the operation started until it was over, not once did all that come into play. Honestly, when the boss says, ‘It’s okay for you to do this thing that requires your hands inside of me,’ that’s a bond that is difficult to put into words in a way that most people would understand.”

While the hepatitis C heart program quickly has become routine in transplantation, Dr. Montgomery focused first on his recovery and then locked in on the next innovation in transplantation.

“Waiting in the ICU, I kept thinking about this paradigm that we’ve been under in transplantation for so long, which is that somebody has to die for someone else to live,” he said. “That came into focus in a new way when I experienced it myself. That was the moment when I said, ‘We’ve got to figure something else out.’”

When Pigs Fly…

“It was such a long shot that I survived everything that I really began to think there was some purpose, that I still had a purpose,” Dr. Montgomery said. “After the transplant, I was already thinking about what I would have to do to take that next step. It was like I was training for an Olympic event, and I had a new energy, a new focus.”

Xenotransplantation is not new. In the 1980s, an infant born with a fatal heart condition, Baby Fae, died within a month of receiving a baboon heart. Later attempts involving nonhuman primates receiving pig organs failed. But advances in gene editing and cloning techniques, specifically the gene-editing CRISPR technology, gave new life to the prospects of xenotransplantation.

Before his transplant, Dr. Montgomery attended the Kennedy Center Honors with his wife, an accomplished opera singer. He caught wind that Martine Rothblatt, the CEO of the biotech firm United Therapeutics (UT), would be in attendance and sought her out before the event. A day later, he and Rothblatt talked for 4 hours about xenotransplantation.

UT develops technologies that expand the availability of transplantable organs. Rothblatt, the founder of SiriusXM radio, sold that company to launch UT and successfully develop a cure for her daughter’s pulmonary hypertension.

“The work Rothblatt and her company had been doing dovetailed so nicely with the work I’d been doing and the work I wanted to do. I had so much of the transplantation knowledge, and they had genetically altered pigs. We just got to work and made a plan,” Dr. Montgomery said.

That plan—a complex marriage of regulatory, governmental, medical, and technological elements—unfolded over 4-plus years, and came to fruition September 25, 2021, when Montgomery performed the first successful pig-to-human kidney transplant. The groundbreaking surgery triggered an avalanche of interest, research, and other procedures. Dr. Montgomery predicts that pig-to-human xenotransplantation will become commonplace within 10 years.

“I’m not sure that without my own transplant, I would have had the fire to move xenotransplantation along that quickly,” he said. “It was truly a partnership, but any partnership is only as strong as its weakest participant. Getting a heart positive for hepatitis C, having that work, and knowing that we need to change the death-for-life paradigm, that inspired me to do the work for myself to be healthy and also be strong enough to achieve the next big thing in transplantation.”

Following his xenotransplantation operation, another team of surgeons, led by Bartley P. Griffiths, MD, FACS (see the June 2022 issue of the Bulletin), successfully transplanted a pig heart into a human. Research from those operations alone will help kickstart clinical xenotransplantation and push it through myriad ethical and regulatory issues.

“He Functions in a Different Place”

From his second-grade conflicts with the nuns to his own heart transplant and beyond, Dr. Montgomery has not only forged a unique path, but he’s also traveled it differently than others would.

“Dr. Montgomery, he’s one of these people that functions in a different place than the rest of us,” Dr. Smith said of his mentor. “He is really not bound by the same expectation or limitations that a lot of us operate under. There is this group of people in medicine, and probably in the world, who can see opportunity where other people see reasons that it won’t work. That has been Dr. Montgomery’s modus operandi for as long as I’ve known him.”

Perhaps the rules do not apply to Dr. Montgomery, especially when he is focused on rewriting them.